“From the last chapter the reader will recall Michael Rappengluck’s work

on the zodiacal constellation of Taurus, depicted at Lascaux some 17,000 years

ago as an auroch (ancient species of wild cattle) with the

six visible stars of the Pleiades on its shoulder”.

Graham Hancock

Already I (Damien

Mackey) touched upon some of Michael Rappengluck’s archaeoastronomical insights

about the Lascaux cave depictions in the first of my multi-part series:

The date for Lascaux

as given here by Graham Hancock in his book Magicians

of the Gods (2015), I personally would consider to be thousands of years too

early.

That same book I

was reading - and generally enjoying - last night and came upon this section

most relevant to my series and to the findings of Michael Rappengluck:

Neolithic

puzzle

[Paul]

Burley’s paper is entitled “Göbekli Tepe: Temples Communicating an Ancient

Cosmic Geography.” He wrote it originally in June 2011

… in February 2013 he asked me to read his paper, which he said concerned

“evidence of a zodiac on one of the pillars at Göbekli Tepe.” I read it,

replied that I found it “very persuasive and interesting, with significant

implications” ….

“Significant

implications,” I now realize as I read through the paper again in my hotel room

in ŞanlIurfa, was a huge understatement. But I didn’t make my first

visit to Göbekli Tepe until September 2013 and by then, clearly, I’d forgotten

the gist of Burley’s argument, which focuses almost exclusively on Enclosure D

and on the very pillar, Pillar 43, that I’d been most interested in when I was

there.

My

interest in it had been sparked by Belmonte’s suggestion that the relief

carving of a scorpion near its base (which the reader will recall was hidden by

rubble that Schmidt refused to allow me to move) might be a representation of

the zodiacal constellation of Scorpio. ….

Here’s

where he gets to his point:

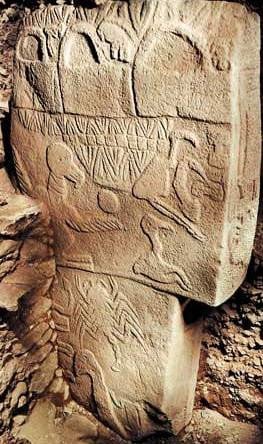

One

of the limestone pillars [in Enclosure D] includes a scene in bas relief on the

upper portion of one of its sides. There is a bird with outstretched wings, two

smaller birds, a scorpion, a snake, a circle, and a number of wavy lines and

cord-like features. At first glance this lithified menagerie appears to be

simply a hodgepodge of animals and geometrical designs randomly placed to fill

in the broad side of the pillar.

The

key to unlocking this early Neolithic puzzle is the circle situated at the center

of the scene. I am immediately reminded of the cosmic Father—the Sun. The next

clues are the scorpion facing up toward the sun, and the large bird seemingly

holding the sun upon its outstretched wing. In fact the sun figure appears to

be located accurately on the ecliptic with respect to the familiar

constellation of Scorpio, although the scorpion on the pillar occupies only the

left portion, or head, of our modern conception of that constellation. As such

the sun symbol is located as close to the galactic center as it can be on the

ecliptic as it crosses the galactic plane.

….

Burley

then presents a graphic that “illustrates the crossing of the galactic plane of

the Milky Way near the center of the galaxy, with several familiar

constellations nearby.” A second graphic shows the same view with the addition

of the ancient constellations represented on the pillar:

Note

that the outstretched wings, sun, bird legs and snake all appear to be oriented

to emphasize the sun’s

path along the ecliptic … The similarity of the bas relief to the

crossing of the ecliptic and galactic equator at the center of the Milky Way is

difficult to reject, supporting the possibility that humans recognized and

documented the precession of the equinoxes thousands of years earlier than is

generally accepted by scholars … Göbekli Tepe was

built as a symbolic sphere communicating a very ancient understanding of world

and cosmic geography. Why this knowledge was intentionally buried soon

afterward remains a mystery.

….

As I sit in my hotel room in ŞanlIurfa in July

2014 spinning the skies on my computer screen, I’m coming more and more to the

conclusion that Paul Burley has had a genius insight about the scene on Pillar

43 at Göbekli Tepe. Burley’s language in his paper is careful—almost diffident.

As we saw in Chapter Fourteen, he says that “the sun figure appears to be

located accurately on the ecliptic with respect to the familiar constellation

of Scorpio.” He speaks of other “familiar constellations” nearby.

And he draws our attention to the

large bird—the vulture—“seemingly holding the sun upon an outstretched wing.”

He does not say which constellation

he believes the vulture represents, but the graphics he includes to reinforce

his argument leave no room for doubt that he regards it as an ancient

representation of the constellation of Sagittarius. ….

We’ve already seen that there is

evidence for the identification of constellations going far back into the Ice

Age, some of which were portrayed in those remote times in forms that are

recognizable to us today.

From the last chapter the reader will

recall Michael Rappengluck’s work on the zodiacal constellation of Taurus,

depicted at Lascaux some 17,000 years ago as an auroch (ancient species of wild

cattle) with the six visible stars of the Pleiades on its shoulder.

Acknowledging such surprising

continuities in the ways that some constellations are depicted does not mean

that all the constellations we are familiar with now have always been depicted

in the same way by all cultures at all periods of history. This is very far

from being the case. Constellations are subject to sometimes radical change

depending on which imaginary figures different cultures choose to project upon

the sky. For example, the Mesopotamian constellation of the Bull of Heaven and

the modern constellation of Taurus share the Hyades cluster as the head, but in

other respects are very different. …. Likewise the

Mesopotamian constellation of the Bow and Arrow is built from stars in the

constellations that we call Argo and Canis Major, with the star Sirius as the

tip of the arrow. The Chinese also have a Bow and Arrow constellation built

from pretty much the same stars but the arrow is shorter, with Sirius forming

not the tip but the target. ….

Even when constellation boundaries

remain the same from culture to culture, the ways in which those constellations

are seen can be very different.

Thus the Ancient Egyptians knew the

constellation that we call the Great Bear, but represented it as the foreleg of

a bull. They saw the Little Bear (Ursa Minor) as a jackal. They depicted the

zodiacal constellation of Cancer as a scarab beetle. The constellation of

Draco, which we see as a dragon, was figured by the Ancient Egyptians as a

hippopotamus with a crocodile on its back. ….

There can therefore be no objection

in principle to the suggestion that the constellation we call Sagittarius, “the

Archer”—and depict as a centaur man-horse hybrid holding a bow with arrow

drawn—could have been seen by the builders of Göbekli Tepe as a vulture with

outstretched wings.

I spend hours on Stellarium toggling

back and forth between the sky of 9600 BC and the sky of our own

epoch, focusing on the region between Sagittarius and Scorpio—the region Burley

believes is depicted on Pillar 43—and looking at the relationship of the sun to

these background constellations.

The first thing that becomes clear to

me is that a vulture with outstretched wings makes a very good figure of

Sagittarius; indeed it’s a much better, more intuitive and more obvious way to

represent the central part of this constellation than the centaur/archer that

we have inherited from the Mesopotamians and the Greeks. This central part of

Sagittarius (minus the centaur’s legs and tail) happens to contain its

brightest stars and forms an easily recognized asterism often called the

“Teapot” by astronomers today—because it does resemble a modern teapot with a

handle, a pointed lid and a spout. The handle and spout elements, however,

could equally effectively be drawn as the outstretched wings of a vulture,

while the pointed “lid” becomes the vulture’s neck and head.

It is the outstretched wing in front

of the vulture—the spout of the teapot—that Burley sees as “holding the sun,”

represented by the prominent disc in the middle of the scene on Pillar 43.

….

Figure

49: A vulture with outstretched wings makes a much better, more intuitive and

more obvious way than an archer to represent the bright, central “Teapot”

asterism within the constellation of Sagittarius.

….

….

But the vulture and the sun are only

two aspects of the complex imagery of the pillar. Below and just a little to the

right of the vulture is a scorpion.

Above and to the right of the vulture

is a second large bird with a long sickle-shaped beak, and nestled close to

this bird is a serpent with a large triangular head and its body coiled into a

curve. A third bird, again with a hooked beak, but smaller, with the look of a

chick, is placed below these two figures—again to the right of the vulture,

indeed immediately to the right of its extended front wing. Below the scorpion

is the head and long neck of a fourth bird. Beside the scorpion, rearing up, is

another serpent.

Part of the reason for my growing

confidence in Burley’s conclusion, though he makes little of it in his paper,

is that these figures, with only minor adjustments, compare intriguingly with

other constellations around the alleged Sagittarius/vulture figure.

First and foremost, there is the

scorpion below and a little to the right of the vulture, which we’ve seen

already has an obvious resemblance to Scorpio, the next constellation along the

zodiac from Sagittarius. Its posture and positioning are wrong—we’ll look more

closely into the implications of this in a moment—but it’s there and it is

overlapped by the tail end of the constellation that we recognize as Scorpio

today.

Secondly,

there’s the large bird above and to the right of the vulture with the curved

body of a serpent nestled close to it. These two figures are in the correct

position and the correct relationship to one another to match the constellation

we call Ophiuchus, the serpent holder, and the serpent constellation, Serpens,

that Ophiuchus holds.

Thirdly, immediately to the right of

the extended front wing of the vulture there’s that other bird, smaller, like a

chick, with a hooked beak. I email Burley about this, and about the different

position and orientation of the scorpion on the pillar and the modern

constellation of Scorpio, and we arrive, after some back and forth, at a

solution. Constellation boundaries, as the reader will recall, are not

necessarily drawn in the same place by all cultures at all periods and it’s

clear that there’s been a shift over time in the constellation boundaries here.

The chick on Pillar 43 appears to have formed a small constellation of its own

in the minds of the Göbekli Tepe astronomers—a constellation that utilized some

of the important stars today considered to be part of Scorpio. The chick’s

hooked beak is correctly positioned, and its body is the correct shape, to

match the head and claws of Scorpio. ….

Fourthly, beside the scorpion on

Pillar 43 is a serpent and beneath the scorpion are the head and long neck of

yet another bird, with a headless anthropomorphic figure positioned to its

right. The serpent matches the tail of Sagittarius (as we’ve seen, the vulture

appears to be composed from the central part of Sagittarius only—the Teapot—so

this leaves the remainder of the constellation available to the ancients for

other uses). The best contenders for the bird, and for the peculiar little

anthropomorphic figure to its right are parts of the constellations we know

today as Pavo and Triangulum Australe. The remainder of Pavo may be involved

with further figures present on the pillar to the left of the bird.

As is the case with Sagittarius,

elements of the modern constellation of Scorpio have been redeployed in the

ancient constellations depicted on Pillar 43. Only the tail of our Scorpio is

in the correct location to match the scorpion on Pillar 43 and its head faces

to the right, whereas the head of the scorpion on the pillar faces to the left.

The scorpion on the pillar is also

below the vulture, whereas modern Scorpio is a very large constellation lying

parallel and to the right of Sagittarius.

I suggest the solution to this

problem is that the scorpion on Pillar 43 is conjured from a combination of the

tail of the modern constellation of Scorpio (right legs of the Pillar 43

scorpion), an unused part of the “Teapot” asterism of Sagittarius (right claw

of the Pillar 43 scorpion) and the constellations that we know as Ara,

Telescopium and Corona Australis (respectively the tail, left legs and left

claw of the Pillar 43 scorpion). Meanwhile, as noted above, the claws and head

of the modern constellation of Scorpio have been co-opted to form the chick

with the hooked beak on Pillar 43.

This whole issue of the relationship

between the modern constellations of Scorpio and Sagittarius and the scorpion

and vulture figures depicted on Pillar 43 takes on a new level of significance

when we remember that in some ancient astronomical figures Sagittarius is

depicted not only as a centaur—a man-horse—but also as a man-horse hybrid with

the tail of a scorpion, and sometimes simply as a man-scorpion hybrid. …. On

Babylonian Kudurru stones (often referred to as boundary stones,

although it is likely that their function has been misunderstood …) a figure of a man-scorpion drawing a bow frequently

appears that “is universally identified with the archer Sagittarius.” …. What further

cements the identification of Sagittarius with the vulture on Pillar 43 is that

these man-scorpion figures from the Babylonian Kudurru stones are very

often depicted with the legs and feet of birds. …. Moreover, in some representations a second scorpion appears

beneath the body—i.e. beneath the Teapot asterism—of Sagittarius … reminiscent

of the position of the scorpion on Pillar 43 (see Figures 50 and 51).

Figure 51: Man-scorpion

Sagittarius figures from Bablylonian Kudurru stones (left) are frequently

depicted with the legs and feet of birds, further strengthening the

identification of the vulture figure on Pillar 43 with Sagittarius. In other

Mesopotamian representations (right) we see a second scorpion beneath the body

of Sagittarius occupying a similar position to the scorpion on Pillar 43.

….

When

all this is taken together

it goes, in my opinion,

far beyond anything

that can be explained away as mere “coincidence.”

The implication is that ideas of how certain constellations should be depicted

that were expressed at Göbekli Tepe almost 12,000 years ago [sic], including

the notion that there should be a scorpion in this region of the heavens, were

passed down, undergoing some changes in the process, but nonetheless surviving

in recognizable form for millennia to find related expression in much later

Babylonian astronomical iconography. But given the close connections with

ancient Mesopotamia, its antediluvian cities, its Seven Sages and its flood

survivors washed up in their Ark near Göbekli Tepe, we should perhaps not be

too surprised.